By Friedrich Bargideon

The Road from Harfleur

The siege had broken us more than it had the French. When we left Harfleur, the ground behind still smoked from the fires of surrender. Half of Henry’s army remained behind, sick or dead. The rest marched north, a column of ghosts dragging itself through rain and mud toward Calais. I felt the familiar heaviness of Providence pressing on me—the quiet recognition that the lesson had not yet been learned.

I had walked these kinds of roads before: Russia, Prussia, Norway, now Normandy. Different centuries, same earth. The wheels of the baggage carts sank deep into the clay; horses fell and were butchered for meat. Men joked that the mud wanted to keep us for itself. In truth, it already had.

Henry rode among his men, helm off, the crown of England bound by a strip of leather. His face had thinned; the confident prince of Harfleur was now a pilgrim to whatever judgment waited ahead. I walked beside the archers, listening to their talk—about pay they’d never see, families they’d never return to. God had sent me among them not to comfort, but to witness.

Across the Somme

The French army shadowed us like a storm building beyond the horizon. We tried to cross the Somme near Abbeville, but every ford was guarded. Henry turned east, seeking a crossing where none waited to kill us. The march grew longer, food scarcer. The dysentery from Harfleur still gnawed at bellies; men bled from both ends and cursed God between gasps.

When we finally found an unguarded crossing at Blanchetaque, I waded through the cold water beside men who prayed aloud even as the current dragged them. I remembered another crossing once—Narva, in snow, when the river froze beneath my boots. Different century. Same fear.

Each night I looked up at the same stars, unchanging sentinels over mankind’s repeating folly. I spoke quietly into the dark: “You’ve sent me here again, Lord. Tell me what lesson remains untaught.” The only answer was wind.

The Shadow of the French Host

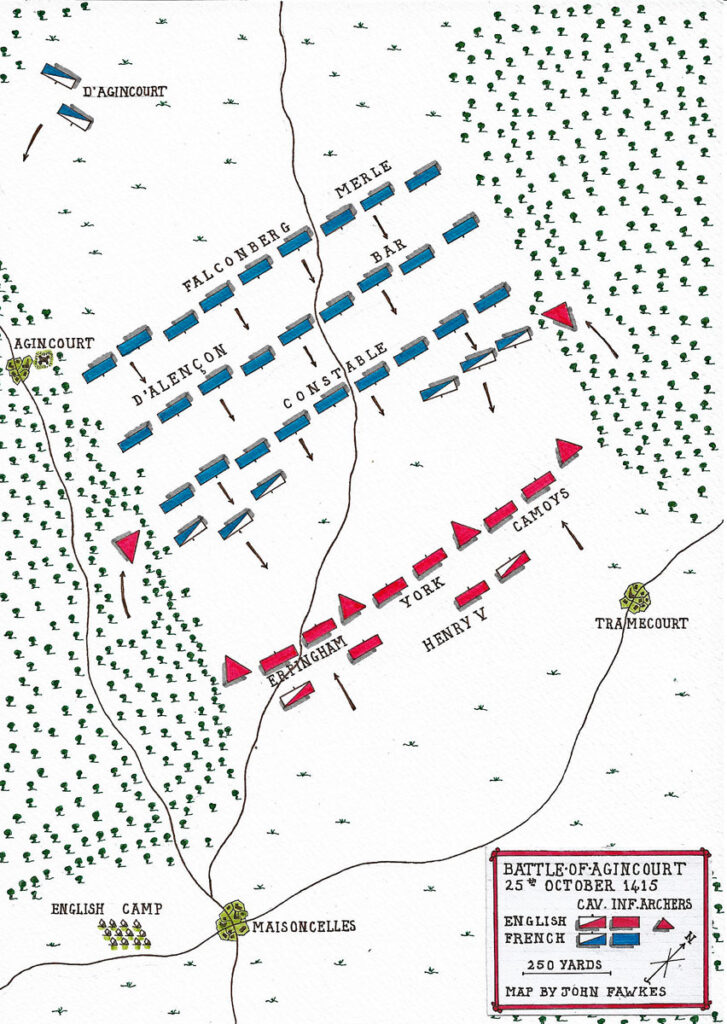

By late October we neared the village of Maisoncelles. Scouts returned breathless—French banners everywhere. The Constable d’Albret and his nobles had assembled their hosts across the narrow field near Agincourt. Twelve, perhaps fifteen thousand strong, bright armor glinting through the rain.

Henry’s men numbered fewer than six thousand. Most were archers, lean and hollow from the march. We camped in the open, our only walls the woods on either side. The rain came again, steady and cold, soaking the feathers of the arrows and the hearts of those who would loose them.

I walked the perimeter that night, taking notes by lantern light. The ground was ploughed for winter wheat—soft, deep, fatal for horses. I could almost feel Providence in it, reshaping the field itself to humble pride. I had seen this before—terrain as divine arbiter, where power turns to panic.

The Eve of St. Crispin’s Day

The French sang and drank in their tents, certain of victory. We sat in silence. Henry moved among his men, speaking not as a king but as a fellow soul facing death. I heard fragments of his words: faith, brotherhood, England. No talk of glory—only survival.

As he passed, our eyes met. He nodded to me as if recognizing something he couldn’t name. Perhaps he saw in my face the knowledge of what was coming. I whispered, “You will win, but the ground will remember every footstep.”

That night I could not sleep. The rain ceased just before dawn, leaving the field slick and glistening. I sharpened my quill and wrote one line in my journal: Every century ends the same—mud, pride, and prayer.

The Measure of Arrows

At first light on October 25, 1415, the English line formed—three divisions across a strip of ground no wider than a bowshot. The French stretched opposite, their knights in gleaming ranks, horses stamping impatiently. Trumpets called, but no one moved. Then Henry ordered the advance.

The archers stepped forward, planted their stakes, and drew. The first volley rose like a flock of black birds and fell into the French vanguard. The sound was not thunder but a thousand small sighs—the breath leaving men who never saw where death came from.

The French cavalry charged, spurred by pride, and met the sharpened stakes head-on. Horses screamed; armor sank; men tripped over the fallen and were crushed. Behind them the second wave stumbled into the first. I stood on a rise and watched the valley of chaos unfold. I had seen tank columns break the same way at Kursk—steel choking on mud.

Henry fought on foot beside his standard, sword flashing dull in the weak sun. He was struck once on the helm but did not fall. Around him, archers abandoned bows and fought with mallets and knives. I moved among them, recording what I could, though each stroke of the pen felt like a betrayal of the dying.

One archer looked up from the melee, face streaked with mud and blood. “We are few,” he said. “Does God count us still?” I had no answer. The arrows had spoken for Him.

The Silence After Victory

By noon it was finished. The French nobility lay in heaps—dukes, counts, men who believed armor could outlast humility. The English too weak to cheer stood amid the wreckage, half in awe, half in disbelief. Henry knelt in the mud and prayed aloud, giving thanks. I joined him, though my prayer was heavier. “You have shown them, Lord, but they will forget again.”

Later came the orders to kill the prisoners. Fear of renewed attack, they said. I watched as captives were cut down where they knelt. The field that God had already judged became a slaughterhouse of caution. No one sang that night.

The Weight of Providence

As dusk settled, I walked the field alone. The mud clung to my boots, thick with blood. Feathers from broken arrows drifted like snow. I thought of Harfleur, of Kursk, of all the places where I had stood between man and his own reflection. Providence governs all, but it does not absolve.

I wrote my final note for the day: The world will remember the name Agincourt, but Heaven will remember the silence that followed.

The king would march to Calais, hailed as chosen. I would move with him until Providence whispered again and pulled me elsewhere—another century, another lesson unlearned. I no longer dread that summons. I only dread that mankind will never listen.

Field Notes & Historical Sources

– Battle of Agincourt fought 25 October 1415 between King Henry V of England and the French under Constable Charles d’Albret.

– English forces ~6,000 (approx. 5,000 longbowmen); French ~12–15,000.

– Terrain: narrow ploughed field between Tramecourt and Agincourt woods; rain preceding the battle turned soil to deep mud.

– English archers deployed stakes to break cavalry; three successive French attacks failed.

– Casualties: French 7,000–10,000 dead, including much of the nobility; English fewer than 500.

– Aftermath: Henry’s army marched to Calais, returned to England as victors; the campaign secured his claim to France but foretold more wars to come.

End of Part II – Agincourt: The Measure of Arrows